Saint Mary’s Church in Saltvik is situated by the rivulet Kvarnbäcken in Kvarnbo, in the middle of the richest Iron Age area of Åland, surrounded by several large graveyards.

The adjacent largest Iron Age graveyard, Johannisberg, shows that Kvarnbo was the central place in Åland during the Viking Age. It also indicates unbroken continuity of settlement and cult well into the medieval period. The settlement connected to Johannisberg was probably situated in the middle of the great area of black earth where the church stands. Traces of houses from the Viking era have been found in this area, both in the churchyard and below the church.

Exterior from the southeast.

The exterior

The church of Saltvik is built of red granite (rapakivi), with large window openings to the north and south. It has no visible outer socle. A small sacristy is joined to the nave. Further additional units are the porch in the south and the west tower. Joints in the walls show that the porch and the tower are secondary additions to the nave, while the relation between sacristy and nave is not obvious from the exterior. With its light plaster coating, the polygonal* apse facing east differs from the other façades. East of the porch a walled-in priest door leading directly into the chancel is visible. The middle window of the southern façade is partly concealed by the porch. The nave has a total of five large window openings, two facing north and three facing south. Four more windows belong to the apse. A south window forms the only light opening to the high west tower, crowned by a Baroque spire from the middle of the 18th century. The church has two entrances: one in the south gable of the porch and another in the tower portal in the west.

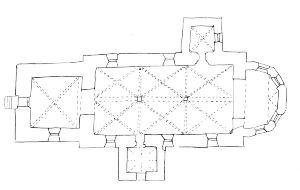

Ground plan.

The ground plan

The rectangular ground plan, with inner measures ca 19.3 x 9.7m includes double naves. Six cross-vaulted bays are resting on two pillars along the central axis. A polygonal chancel was added as a continuation of the central axis towards the east. Similarly, towards the west tower the room opens through a wide and low arch. In front of the southern portal stands a porch. The sacristy can be reached through a portal in the eastern part of the north wall. Towards the south and the north, large window openings cut through the walls of the nave.

Interior towards the east.

The interior

The interior of the church gives a disparate impression, with traces of innumerable alterations. High white rib vaults, cast in modern concrete, rest on slender pillars with square cross sections. The nave opens through a high pointed nave towards the polygonal chancel in the east, and towards the west tower through a lower arch. Various traces of destroyed vaults and fragmentarily preserved wall-paintings make it difficult to interpret iconography and chronology. Thanks to a number of large window openings, the interior is bathed in light. A recessed round-arched framework of brick surrounds the sacristy portal towards the north. It is still possible to discern the traces of an earlier vault lower down on the west gable wall.

The inventory, with medieval artifacts from different centuries, reflects the same variations but the 17th century really dominates the interior. Large areas of the medieval wall paintings were whitewashed to leave space for a total Post-Reformation iconographical program, directed by Dean Boetius Murenius (vicar at Saltvik, 1636-1666). In turn these 17th century paintings have been destroyed. The grand altarpiece from 1662 is a donation from the Footangel family at Germundö Manor, the Footangel family, decorating the church with their coat of arms at the same time. Nowadays the pulpit from 1829 is placed in the southeast corner of the nave. It can be reached through a wall passage from the chancel.

Building history

The remains of a skeleton were found under the northern wall of the present nave during excavations in the 1950s. Thus the site was used earlier as a burial ground and we therefore have to presuppose an older wooden church on the site, although nothing is known about this. The remains of a stave construction, earlier thought to be the remains of a stave church, are more likely part of the earlier Viking Age settlement in the area. Innumerable heavy-handedsecondary interferences make the building history of Saltvik church complicated and hard to interpret. Scientific analysis, however, has thrown some light on the problems:

About 1270-1296 the rectangular nave and sacristy were erected. The church was probably vaulted as soon as the walls had hardened. Remains of this first vaulting along the walls demonstrate that these vaults were not very high. Narrow and highly placed windows formed light openings, three towards the south and two towards the east. The northern wall lacked windows. The main altar stood free from the east wall, further towards the middle of the chancel. To begin with, the church had at least two side altars, one for Mary in the north, west of the sacristy portal, and another in the south, immediately west of the priest door leading into the chancel.

Dendrochronological analysis shows that large architectural alterations were performed at the end of the 14th century. For reasons unknown, the original fieldstone vaults of the double naved construction were now torn down, only to be replaced by other vaults a few decades later, this time in brick. Among other changes was the erection of the porch in front of the main portal of the nave in the 1370s. Soon after, in 1381, the west tower was constructed in one singular building phase up to the pyramidshaped wooden spire. A rounded arch was opened between nave and tower in connection with the building of the tower. Large side altars were added in front of each central pillar. Walls and vaults were covered by paintings in the 15th century.

The post reformation period

Detail of the northern chancel wall, with Post-Reformation wall paintings.

In the beginning of the 16th century, following the Reformation, the church was left in disrepair. Probably most of the medieval wooden sculptures of the church were lost during this period, among others the Madonna sculpture, which must have adorned the northern side altar in this church devoted to Mary. According to the Lutheran liturgy, the interior was completely renewed with a new pulpit, pews, and a gallery along the west wall. From the 1630s onwards the books of accounts and the visitation records provide evidence of what was done. All the side altars were removed and the earlier freestanding high altar was moved against the eastern wall. Large parts of the medieval wall paintings had to give way to a Lutheran painting program, executed by Master Mårten Johansson. The initiative came from Boetius Murenius.

Minor architectural alterations were made in the 17th and 18th centuries. A window towards the north was opened in the 1830s to improve the readability in the gallery. But truly radical changes were not made until the 1850s, when the medieval brick vaults were torn down and replaced by a flat wooden barrel vault. The polygonal chancel was added in the east at the same time, and large parts of the eastern gable were torn down, including the original chancel windows. A triumphal arch through the former chancel wall was opened up to the new chancel. Further, all the windows were enlarged, conforming to the windows in the new chancel. The court painter Robert Wilhelm Ekman painted a new altarpiece representing “Christ in Gethsemane” acquired in 1862.

After archaeological excavations, the church was once more extensively renovated and rebuilt in the 1950s. Yet another demolition of the inner ceiling was performed when new double-nave vaults cast in concrete replaced the wooden barrel vault. Whatever was left of earlier wall paintings was uncovered and restored, and the altarpiece from 1662 was moved back to the high altar. The architect in charge was Ruben Lindgren.

Inventory

There are only random survivals of the medieval inventory of the church.

The crucifix on the south wall has a rare shape. The little aediculae at the end of the cross arms have only one parallel: the crucifix from nearby Sund, from the middle of the 13th century. Like in Sund the cross consists of local wood, this time of poplar. Dendrochronological dating of a pine board supporting the back of the cross-center yields the 1250s.

The font, quatrefoil from top to bottom, is a piece of high quality imported from Gotland in the middle of the 13th century. Even if there are several parallels to the font in Sweden, it is unique in Finland. It is well cut and highly polished and carved from so-called Hoburg marble.

The silver chalice and paten, a donation made in 1346 by Laurentius Arnbernini (canice at Turku Cathedral) for ”his church Saltvik”.

Altare Domini”, the corpus of an altarpiece from the 15th century, hangs today on the north side of the triumphal arch. Side wings, with sculptures in double rows, are missing. Single figures from the wings were integrated into the corpus, when it received its present appearance in the 17th century. The motif is the crucifixion of Christ, including the two robbers and the mourning Mary and John.

From the Post-Reformation era:

Saint George and the dragon, 2.38 x 3.10 m, oil on panel, was painted by Mårten Johansson in 1659. Again, the initiative came from Boetius Murenius. Today the painting hangs on the northern wall of the tower’s ground floor. The model is the well-known Equestrian group in the Great Church of Stockholm, with the same motive. This group from 1489 honors Sten Sture, Senior, for the victory at Brunkeberg, when he defeated an invading force led by Christian I of Denmark.

A new altarpiece was donated to the church by the Footangel family in Germundö in 1666, sculpted by Mathias Reiman.